Most recent estimates from the World Health Organization show that globally, 149.2 million children under the age of 5 years of age are stunted (too short for their age) and 45.4 million are wasted (underweight for their height). Around 45% of deaths among children under 5 years of age are linked to undernutrition, mostly occurring in low- and middle-income countries. In addition to physical detriment, poor nutrition also impairs the mental development of millions of children. The Nutrition team at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) is focused on the implementation of large-scale food fortification (LSFF) to address micronutrient deficiencies across the globe. A key part of the reliability and sustainability of a system is through compliance monitoring of fortified foods to the country-specific policy and regulatory standards. However, compliance systems have been a weak point in most fortification programs to date, frequently due to poor government monitoring & enforcement (M&E) on account of limited resources and budgets. The START team was asked to create three narrative case studies that reviews and analyzes existing national food fortification programs pertaining to select food vehicles and micronutrients in Chile (wheat with folic acid), Costa Rica (multiple food vehicles and micronutrients), and Guatemala (sugar with Vitamin A). The goal was to ultimately identify successful archetypes in M&E and procedures sustaining adequate levels of fortification.

Chile began mandatory fortification of flour in 1951 through legislation of article 350 of the Sanitary Regulation for Food Products. In 2000, article 350 was amended to add folic acid to the list of required micronutrients. Neural tube defects in newborns, including spina bifida, anencephaly, and encephalocele, are often preventable with folic acid fortification programs implemented with women of child-bearing age in mind. In Chile, the folic acid fortification program has been associated with significant decreases in neural tube defects. A 2004 evaluation conducted by academics sampled bread from 50 randomly selected bakeries in Santiago in addition to analyzing blood samples from volunteers who reported bread consumption. The evaluation found improved folate status in women of childbearing age and also identified a 40% decrease in neural tube disorders from the pre-fortification period to post-fortification, from 17.2 to 10.1 per 10,000 births.

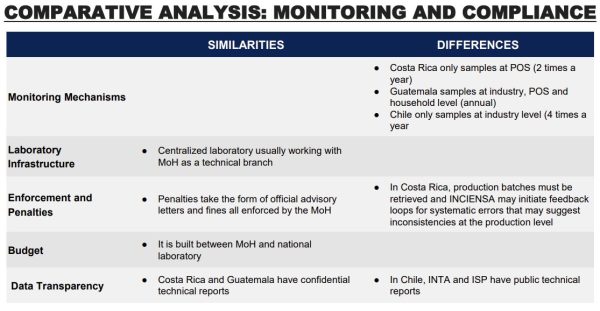

Chile’s national fortification regulations do not prescribe a standard operating procedure for internal monitoring of folic acid at the level of wheat flour production, and there is no national standard for such internal monitoring. The milling sector has strong quality control and assurance systems in place, and mills and milling groups independently developed their own

standards of product production procedures. They are, however, not publicly available. Quality assurance checks rely on what can be learned from analysis of flour samples post-production rather than inspection at the production stage. Ministry of Health regional offices are required to inspect each mill four times a year, with inspectors taking flour samples for analysis. These samples are sent to a central laboratory, the National Reference Laboratory, which analyzes each sample for required micronutrients. Results of these monitoring activities are published every year, disaggregated by region and micronutrient. A review of Ministry of Health records in 2011 indicated significant improvements in food fortification quality over the previous three years, but not all regions were found to be observing the requirement to take samples four times a year from each mill. At that time, 9 of Chile’s 16 administrative regions had been sending fewer than four wheat flour samples a year for analysis. The 2011 report also suggests relatively low compliance with required folic acid levels in acquired samples. Although other micronutrients had higher levels of compliance, including 87% of samples with adequate thiamine levels and 90% with adequate riboflavin levels, just 10% of samples were in the required range for folic acid. Furthermore, fortification compliance varied within each given mill during that time, suggesting issues with consistency. However, this report dates to 2011 and conditions may have changed subsequently.

Costa Rica has been a global model in its fight to improve public health through campaigns on LSFF, strengthening the primary healthcare system, sanitation, deworming, and immunization since the 1930s. The country has had tremendous results in indicators like under 5 mortality, maternal mortality, and life expectancy. Costa Rica's Ministry of Health included food fortification as a strategy in 1973 under the National Health Law. Regional health organizations like PAHO and ILSI have reported the reduction in micronutrient deficiency diseases. The prevalence of goiter due to iodine deficiency was reduced from 18% in 1969 to 4% in 1979; retinol deficiency, which was mostly affecting preschool children, went from 33% in 1966 to 2% in 1981. A study looking at the effect of folic acid fortification found a 51% decrease in prevalence of neural tube defects from the pre-fortification period to the post-fortification period. Finally, a study looking at the effectiveness of the iron fortification program resulted in a reduction of anemia in children from 19% to 4% and in women from 18% to 10%.

In Costa Rice, producers and importers are responsible by law to ensure proper fortification of their product. Each factory may establish qualitative and quantitative monitoring strategies. INCIENSA provides technical support to industry at the beginning of each fortification program around sampling and analysis and has done specific auditing visits to verify the correct storage of some fortification premixes. Ministry of Health and INCIENSA coordinate annual plans to monitor the national fortification program. The Ministry of Health is responsible for the purchase of reagents, equipment, and supplies, while INCIENSA provides the infrastructure, personnel, and basic services. The plan contemplates the number of samples and frequency and every year two samples are taken of all foods that are fortified by law. The Ministry of Health is responsible for scheduling visits in different regions and sampling at the same location occurs approximately every two years. Samples are taken at different shops (supermarket, grocery store, convenience stores and other small stores) and are intended to include all the brands available. At the borders, they include brands that are not brought through custom. The Ministry of Health and INCIENSA are more interested in points of sale (POS) sampling because product rotation and incorrect storage may cause vitamins and mineral degradation even when correct micronutrients levels are registered in the industry. INCIENSA produces real time sample reports that are immediately shared with the ministry of health. The MoH enforces fortification by sending sanitary sanctions to brands that are not complying with fortification levels, they must retrieve the production batch from all POS, and communicate strategies to correct fortification. At the end of the year, a technical report is made for each of the fortified vehicles in which they include a complete analysis of all the samples, behavior of the brands over time, and recommendations.

Guatemala’s commitment to enhancing public health through food fortification dates back to 1974 when the government passed legislation mandating the fortification of all table sugar intended for domestic consumption with 15 retinol equivalents (RE) per gram of sugar. This fortification program has played a pivotal role in significantly reducing the prevalence of vitamin A deficiency in the country. Beyond sugar, Guatemala has extended the scope of mandatory fortification to other staple foods, with micronutrient dosages based on Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) specifically tailored for Guatemalans. The assessment of Guatemala's vitamin A fortification program showed encouraging outcomes. Within six months of consuming fortified sugar, a substantial reduction in the prevalence of low plasma retinol levels was observed. After 12 months, the mean prevalence of low plasma retinol values in the population was less than 5%. The fortification initiative also resulted in a noteworthy 50% decrease in the prevalence of human milk samples with inadequate retinol levels. Advancements in technology enabling the double fortification of sugar with vitamin A and highly absorbable iron tris-glycine chelate presents an opportunity to effectively address iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia.

By Guatemalan law, producers and importers are responsible for ensuring proper fortification of their product. The START team did not find information regarding specific procedures. External monitoring begins with rigorous government inspections to ensure sugar producers adhere to the fortification guidelines outlined in the decree at the industrial level. However, there is no available information regarding the frequency of these inspections. The Ministry of the Economy undertakes thorough verification assessments encompassing fortified foods net content, labeling accuracy, and advertising precision at various POS. The Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance and National Health Laboratory work together in sampling and analyzing micronutrient content at POS. This collective effort guarantees precise information and distribution of fortified sugar to consumers. Regular analysis of Vitamin A content in household sugar samples is a cornerstone of the quality control process. This involves collecting samples during multipurpose annual surveys, allowing authorities to assess the actual fortification levels and determine the extent of population coverage. The household surveillance aspect is carried out through essential programs like the Micronutrient Sentinel School and the Health and Nutrition Epidemiological Surveillance System (SIVESNU). These initiatives provide valuable insights into the actual consumption patterns of fortified sugar among the population, particularly in distant regions not covered by routine regulatory monitoring. Publicly available reports are scarce, mainly co-authored by bilateral organizations such as UNICEF and USAID.

In conclusion, the success of compliance mechanisms for large scale food fortification hinges on the following characteristics: collaborative efforts, robust legislation and consistent funding, and centralized quality control and monitoring. A strong similarity between the three case studies was the existence of collaborative efforts between government bodies, international entities, research institutions and industry, which was as vital to initiate programs and ensure success. Chile, Costa Rica and Guatemala have robust legislation that underpins effective fortification efforts; they include clear roles, standards and penalties that lay the groundwork for accountability and compliance. In the three case studies included in this report, the Ministry of Health is the central agency responsible for enacting and enforcing legislation, moreover they are the coordinating agency for external monitoring, usually involving a national lab that conducts testing. Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Chile follow different procedures for testing in terms of frequency and level in the supply chain; however, since these three programs are considered successful, this suggests that testing design can vary and adapt to a country's needs and expertise. Finally, funding for quality assurance and compliance in Costa Rica and Chile is national and consistent; Guatemala still receives funding from bilateral organizations, especially when fortification is targeted to vulnerable populations. National and consistent funding is a characteristic that makes these programs more likely to succeed.